Articles of Interest

China’s Relations with the World

The world has been witnessing souring U.S.-China relations since 2018, but the U.S. isn’t the only nation whose relations with Beijing have hit a new low. Other Western economies, including Canada, the European Union and the United Kingdom, have sparred with China over a range of issues: human rights, Hong Kong’s new national security law, the origins of the virus, and national security concerns over Chinese technology companies. Beijing has also been embroiled in tensions with its Asian counterparts, including a border dispute with India and a series of defense and foreign policy disagreements with Australia.

All of these tensions have resulted in significant trade frictions that have caused the prospect of confronting China’s trade practices (such as industrial subsidies and forced technology transfer) to gain popularity. However, contrary to populist and protectionist belief, trade wars can be expensive and rarely achieve their objectives.

The U.S.-China trade war serves as the best example. According to recent studies, the trade war has cost the U.S. economy nearly 250,000 jobs, 0.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) and more than $45 billion in tariffs. Uncertainty surrounding the tariffs has pushed businesses to postpone or cancel their investment plans. Retaliatory measures from China have hindered the U.S. agricultural sector and cost taxpayers billions of dollars in supplemental support for farmers.

The trade war has put a dent in the Chinese economy as well. Not only did China give in to some U.S. demands by committing to buying $200 billion more in goods (although it fell short of that target) under the “Phase One” deal, but its exporters had been losing business to alternative suppliers like Taiwan, Vietnam and India before the pandemic. Increased policy interventions and the pre-COVID rollback of deleveraging efforts also indicate how heavily tariffs and trade restrictions have weighed on the Chinese economy.

The trade war has produced neither a lasting change in trade deficits with China nor evidence that manufacturing is being re-shored from Beijing. In fact, on the back of increased demand for goods amid the pandemic, Chinese exports have flourished worldwide. China overtook the U.S. to become the EU’s largest goods-trading partner in 2020 and even concluded negotiations on an investment deal with the bloc. The trade war didn’t cause a structural shift in Chinese policies or supply chains, as reconfiguring value chains is a slow and expensive process. However, the pandemic has added momentum on this front by making clear the importance of resilient supply chains and domestic production.

As with the United States, Beijing’s tensions with Australia and India have spilled over to the economic arena. While the direct cost of tariffs on some Australian exports has been nominal (about $3 billion in lost exports in 2020 out of more than $100 billion in annual exports to China), a lasting severance of trade ties with China would inflict visible damage on the Australian economy. Canberra is more dependent on Beijing than on any other advanced economy in the world, with the latter accounting for nearly 40% of Australian goods exports. That said, the Asian economic powerhouse won’t come out unscathed, should Canberra decide to restrict exports of iron ore. More than half of this raw material for making steel consumed in China is imported from Australia.

Despite tensions, trade between China and Canada has been flourishing. Yet the potential for enhanced trade cooperation has taken a hit as Canada terminated negotiations for a free trade agreement with Beijing late last year. As it stands today, tensions are unlikely to have a major impact on the Canadian economy, as China accounts for only 3.9% of Canadian goods exports. China is not just a manufacturing powerhouse, but has also become the world’s third-largest foreign investor, after the U.S. and Japan. Increasing outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) is part of Beijing’s long-term economic and political strategy—not just for bolstering its own economy through increased exports, but also for leveraging its economic muscle to increase its influence overseas.

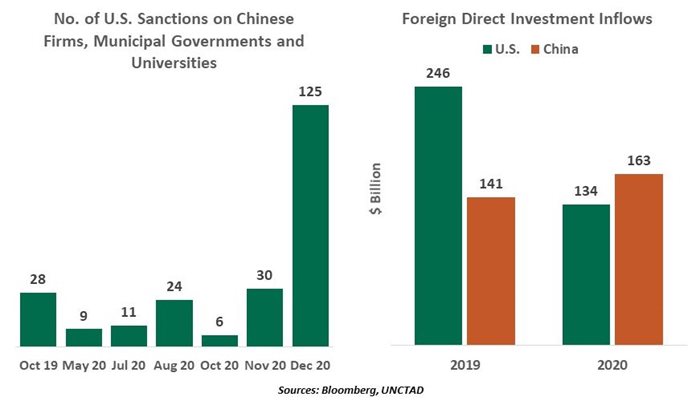

Those goals could take a hit amid worsening trade ties, sanctions and increased suspicions of Chinese investments. Foreign investments, particularly into the U.S. from China, have suffered thanks to more stringent investment screening measures. While Chinese outbound investments are being met with increased scrutiny, China is increasingly seen as an attractive investment destination.

International investors are buying into China’s $15 trillion bond market in increasing numbers. The hunt for higher yields, Beijing’s efforts to liberalize its capital markets, and stronger economic performance have contributed to record inflows. While Western pension funds account for only a small share of foreign investments in yuan bond markets, interest is growing. Of the $9.5 trillion of assets under management from corporate and public pension funds globally, 0.26% was held in Chinese bonds as of the third quarter of 2020, up from 0.04% in 2015. While the pace of China’s economic growth will be slower, it should still be stronger than that of other major advanced economies, leading Chinese investments to remain appealing to many investors.

But, while China may not carry the economic risks typical of emerging markets, it is not riskless.

- China’s high corporate debt and rising defaults in domestic bond markets are concerning.

- Uncertain international relations could continue to weigh on investments in China and its securities. Tensions with the United States have resulted in the expulsion of several Chinese companies from U.S. equity indices and restrictions on U.S. government pension funds investing in China.

- Transparency concerns around some obligors have kept the proportion of Chinese securities in benchmark indices small relative to China’s share of global debt and GDP. China’s debt market is the world’s second-largest after the United States, but foreign investors account for 10% of China’s sovereign debt, compared to one-third of the U.S. Treasury market.

China’s desire to “go global” is understandable, but its approach could hurt its goals. At some point, Beijing will have to re-think how many economic battles it can afford without significantly harming its economy. By punishing its partners, China could lead them to look for better relationships elsewhere.

Vaibhav Tandon, Economist, Global Risk Management division, Northern Trust

Vaibhav Tandon is an Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Vaibhav briefs clients and colleagues on the economy and business conditions, supports internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishes the bank’s formal economic viewpoint. He publishes weekly economic commentaries and monthly global outlooks.

Prior to joining Northern Trust, Vaibhav spent two and a half years as an economist at Société Générale covering the Eurozone market. In his role, Vaibhav tracked and forecasted inflation and labor market developments across the Eurozone economies and published several research reports on the subject. He also published monthly and quarterly global economic updates.

Before Société Générale, Vaibhav worked as a research analyst at Aranca, a global research and analytics company in Mumbai, India.

Vaibhav holds an MSc International Business (Economics) from the Lancaster University, U.K. and a bachelor’s degree in foreign trade from MITSOM College, Pune, India.