Articles of Interest

Long-COVID – in it for the long haul?

Since 2020 we witnessed many evolving and changing concepts relating to COVID-19, one of which is the long-term suffering of symptoms of the disease known as post COVID-19 condition or long-COVID. Defining and explaining what long-COVID is, and what it could mean for future health for many people, is becoming a key focus for many countries as more data points are accumulated. This article provides insight into the prevalence of long-COVID in Canada and the potential longer-term health impacts that are being revealed through research. It also shares thoughts on what long-COVID could mean for future health and longevity, as well as the implications for employers, pension plans, insurers, and the labour market.

What is long-COVID?

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) defines post COVID-19 condition (referred herein as long-COVID) as symptoms persisting or recurring for weeks after acute COVID-19 illness, and further breaks this down into post COVID-19 conditions occurring 4 to 12 weeks (short-term) and greater than 12 weeks (long-term) after COVID-19 diagnosis.

The Government of Canada has provided a list of common long-COVID symptoms in adults which includes fatigue, memory problems, sleep disturbances, shortness of breath, anxiety and depression, general pain and discomfort, difficulty thinking or concentrating, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Various studies have cited fatigue as the most prevalent symptom.

How prevalent is long-COVID?

An article in the Globe and Mail estimated between 25% and 50% of working-age Canadians who have been infected by COVID-19 could have or develop long-COVID symptoms potentially limiting their health or activity for a few months or even permanently.

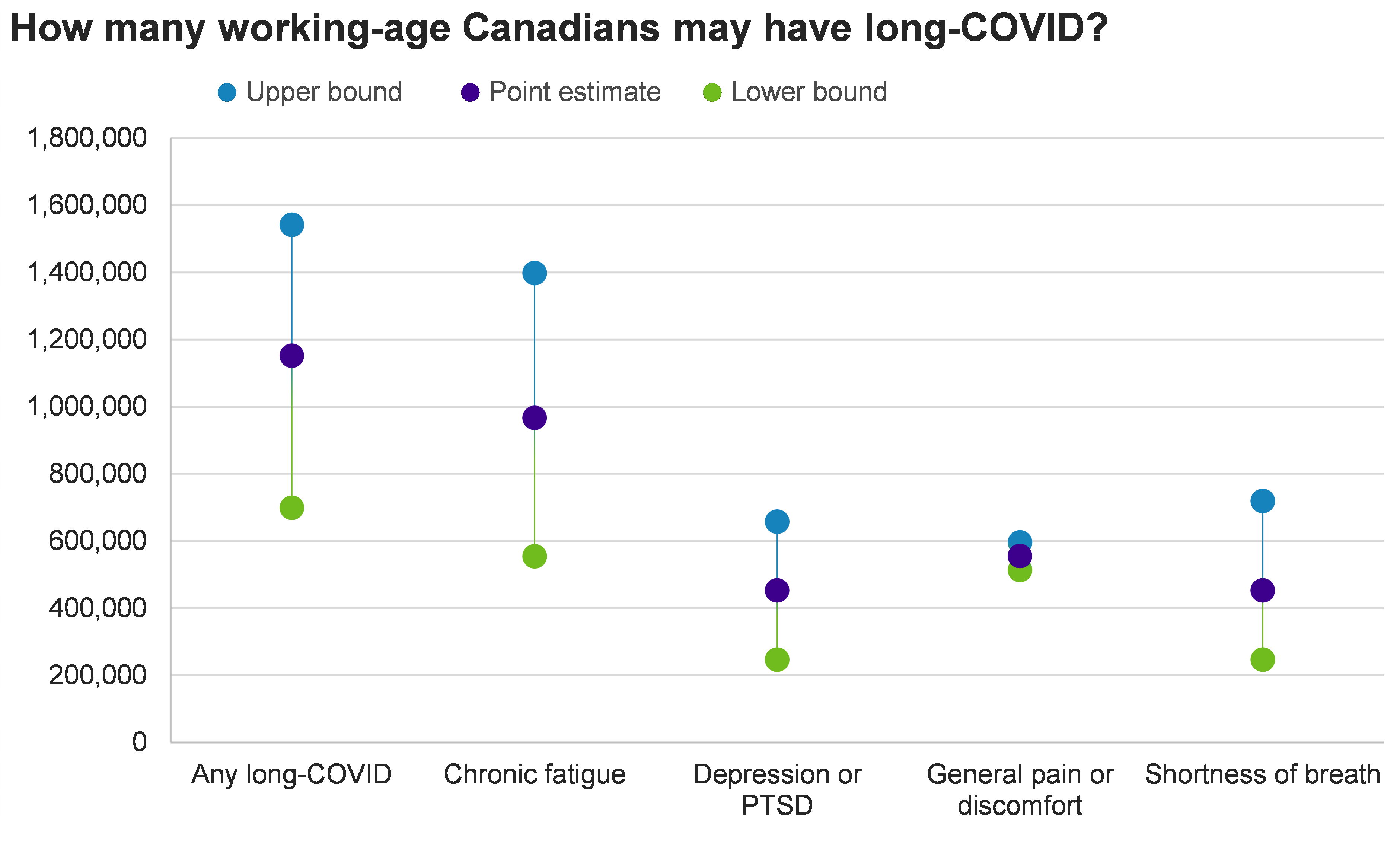

The article estimated around 600,000 working-age Canadians with any long-COVID symptom including around 500,000 with chronic fatigue (their estimates are up to the beginning of December 2021 and before the effects of the Omicron variant). Using the same methodology, we show below the updated estimates as of mid-March 2022 for various long-COVID symptoms.

Source: Original analysis by Jennifer Robson, Associate Professor of Political Management, Carleton University. Calculations using Statistics Canada, Table 13-10-0775-01 Detailed preliminary information on cases of COVID-19, 2020-2022: 4-Dimensions (Aggregated data) and Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. Estimates updated to mid-March 2022 by Club Vita.

A couple of caveats must be made regarding the certainty of these estimates due to the limited data available for this newer disease:

Firstly, the likelihoods of people developing certain symptoms following a COVID-19 infection are derived from a meta-study covering early pandemic analysis. These estimates as of mid-March 2022 reflect the uptick in cases following the appearance of the Omicron variant which epidemiologists often qualify as having less severe symptoms. Considering this, these estimates may be high. Furthermore, studies have not yet qualified the prevalence of long-COVID in terms of vaccination status or different variants of the COVID-19 virus. It will be important to monitor the emerging insights on how these factors impact the prevalence of long-COVID

Secondly, total cases of COVID-19 are not known exactly for various reasons such as scarcity of testing at the start of the pandemic, asymptomatic cases and more recently restrictions on testing eligibility in some provinces. We know that there have been at least 3.3 million cases of COVID-19 in Canada as of mid-March 2022. Therefore, long-COVID has the potential to impact a vast amount of the Canadian population. Results from the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey in the UK show an estimated 1.3 million people in private households reporting symptoms persisting for more than four weeks as of early January 2022 – representing 2.1% of the UK population. The UK results are in line with lower end of the Canadian estimates of the working-age population who may be affected by long-COVID.

Despite these caveats, the magnitude of working-age Canadians suffering from or developing disabilities could still be significant.

What are the longer-term health impacts?

Various studies of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients conducted around the world have shed some light on the potential health implications of long-COVID. A Wuhan study consisted of previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Wuhan and worryingly showed 76% of patients were still experiencing symptoms six months after initial infection. CT scans also showed inflammation on lungs in many patients – likely caused by viral pneumonia. This evidence of organ impairment is further supported by information provided by the UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) which describes a study finding 78% of people with abnormalities showing on cardiovascular imaging 10 weeks after hospital discharge. Another research study of almost 50,000 previously hospitalized COVID-19 patients in England found patients to be at higher risk of a new diagnosis of a respiratory disease, diabetes, or heart disease, compared to somebody who had not been infected with the virus.

Research into the longer-term impacts of COVID-19 is becoming a key focus of many countries, including Canada. One such initiative is the Canadian COVID-19 Prospective Cohort Study (CANCOV) – seeking to better understand the long-term outcomes in COVID-19 patients and their unique characteristics such as genetic and clinical risk factors, functional and neuropsychological status, return to work, and pattern and cost of healthcare utilization. Another initiative established by the Montreal Clinical Research Institute in February 2021 is a post COVID-19 clinic investigating the effects of the virus and subsequent abnormalities. These initiatives are still in the early stages of research.

Further insights into the long-term effects of COVID-19 can be found in a Statistics Canada survey, which shows an increase in employed people with mental health-related disability – 6.4% in 2019 compared to 8.7% in 2021. Statistics Canada suggests that given the large-scale employment losses related to the pandemic, this increase was likely due mostly to an increase in the prevalence of mental health-related disability among those who were already employed, rather than an increase in employment among those with a disability.

It is hoped that further research will increase knowledge of how and why the virus causes some people to suffer long-term effects following a COVID-19 infection to assist in developing effective treatments and social support programs for recovering patients.

Long-COVID and health adjusted life expectancy

Long-COVID has the potential to affect the long-term health of many people. First, the direct potential physical health impact – if symptoms could last months, or years and also develop into other conditions. Second, there is a potential for secondary impacts due to restrictions on normal activities from the symptoms being experienced. For example, people who are suffering from fatigue may reduce their activity and exercise and develop health conditions as a consequence. Fatigue could lead people to reduce work hours or retire earlier, potentially impacting long-term intellectual stimulation and learning which neuroscience research shows can help to prevent dementia.

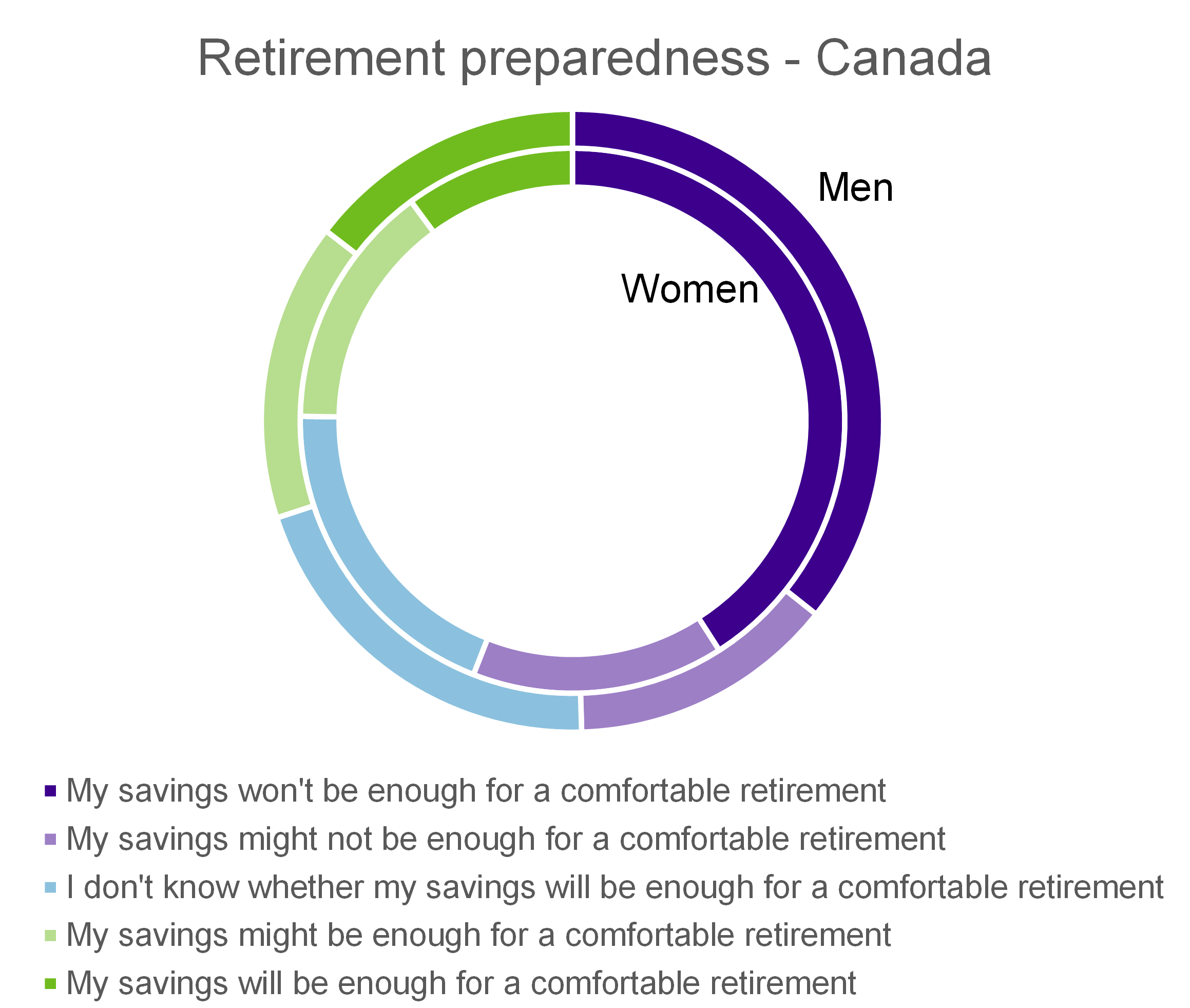

Long-COVID could impact financial health, if the symptoms restrict people’s ability to obtain career advancement, work, or force them into retiring earlier than they planned. This could become an accelerating factor of the pension savings crisis, creating more people retiring with insufficient savings. A recent survey by Club Vita showed over 50% of Canadian respondents felt their savings wouldn’t or might not be enough for a comfortable retirement. Long-COVID has the potential to increase this figure.

Source: Reality Check: Club Vita’s longevity, lifestyle, and retirement perception survey, 2022.

It’s still very early to say the exact effects long-COVID could ultimately have on long-term physical, mental, and financial health (and therefore life expectancy) of those who’ve experienced the condition. However, early studies are asserting multiple long-term health risks and challenges ahead for the so called COVID long-haulers.

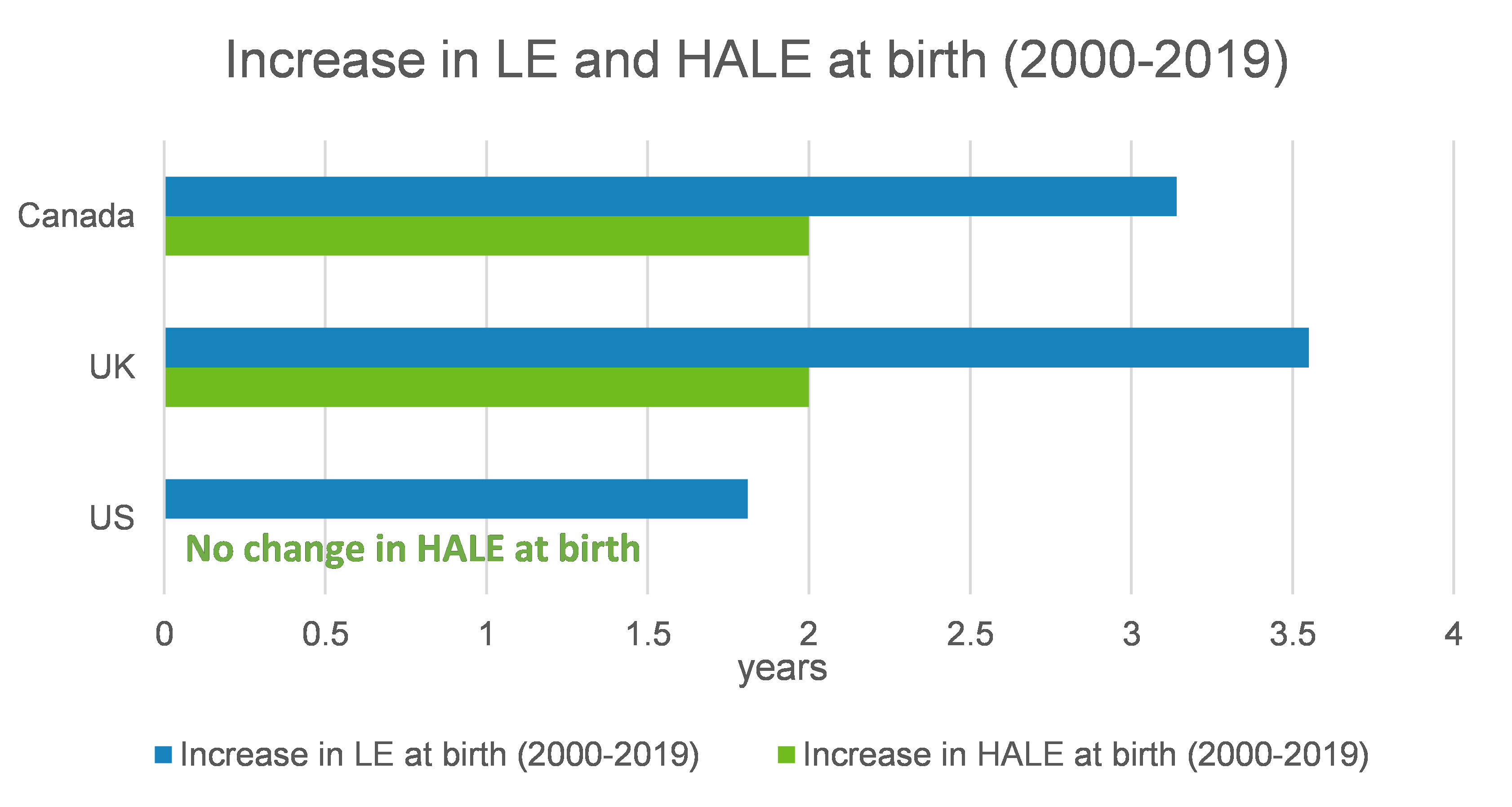

One way to monitor the long-term health of a population is by measuring the changes to health adjusted life expectancy (HALE) which is life expectancy adjusted for years spent in poor health, and represents a broad measure for years of life expected to be lived in good health. We are already seeing a disconnect between increases in HALE and increases in life expectancy – with expected time spent in good health, not keeping pace with the increases in life spans.

Source: World Health Organization, Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy. Downloaded 28 March 2022

Society functions the best when it’s population can stay in good health for as long as possible. Long-COVID has the potential to increase the time people will spend in ill-health. Another aspect we could consider is how life expectancy and HALE already varies by socio-economic groups and how this could be further enhanced with COVID-19 affecting more people in lower socio-economic groups. Monitoring the difference between life expectancy and HALE in the coming years will give us some measure of these emerging trends.

What does this mean for employers, pension plans, insurers, and the labour market?

One could expect an increased prevalence of disability in the workplace stemming from the effects of long-COVID. If this is realized, employers and insurance providers could see greater demand to provide adequate disability coverage for employees who are unable to continue work after being infected with COVID-19 and may incur increased related costs. Already the short-term effects have been considerable for employers. The average hospital stay across all ages in Quebec is 15 days, extending to 22 days for those also admitted to an intensive care unit. This highlights that the short-term disability costs for an employer could be significant, accounting both for employees’ hospital stay and recovery time at home.

As part of their risk management framework, many pension plan trustees and sponsors are considering the additional longevity risk as a consequence of the pandemic. Long-COVID has the potential to increase the volatility of longevity risk for a pension plan and therefore should be monitored and considered within this framework. Pension plans could also see the effects of heavier mortality due to more instances of long-term disability. Club Vita’s research shows the period life expectancy at age 65 for a disabled pensioner is lower by at least 4 years for males and females compared to a normal health pensioner, we will need to monitor emerging experience to see whether this is true for those affected by long-COVID.

As well, if long-COVID influences long term improvements in life expectancy, we could see countries that have kept the pandemic more under control, such as Canada, having stronger improvements than ones that have been more severely affected such as the UK and US, leading to a potentially greater divergence in life expectancy projections between nations.

Finally, another aspect to consider is the effect of long-COVID on the Canadian labour market and economy. Using the lower end estimate (as of mid-March 2022) of approximately 700,000 working-age Canadians suffering long-COVID, this would account for almost 2.8% of all working-age Canadians. Therefore, long after we have gone back to our “new normal” life, we may see significant effects on the labour market if long-COVID affects working practices, productivity, and participation, which can ultimately have negative economic implications.

References

- Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, Understanding the Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID) and the Expected Burden for Ontario, https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.44.1.0.

- Government of Canada, Post COVID-19 condition, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/symptoms/post-covid-19-condition.html.

- Public Health Ontario, Persistent Symptoms and Post-Acute COVID-19 in Adults – What We Know So Far, https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/covid-wwksf/2020/07/what-we-know-covid-19-long-term-sequelae.pdf.

- The Globe and Mail, Seven charts that provide a glimpse of Canada’s labour market in the year ahead, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-charts-jobs/.

- Domingo FR, Waddell LA, Cheung AM, et al. Prevalence of long-term effects in individuals diagnosed with COVID-19: A living systematic review, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.03.21258317.

- Government of Canada, COVID-19 daily epidemiology update, https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html.

- Office for National Statistics, Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 3 February 2022, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/3february2022.

- The Conversation, How many people get ‘long COVID’ – and who is most at risk? https://theconversation.com/how-many-people-get-long-covid-and-who-is-most-at-risk-154331.

- National Institute of Health Research, Living with Covid19 – Second review,https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/themedreview/living-with-covid19-second-review/.

- Canadian COVID-19 Prospective Cohort Study (CANCOV), https://cancov.net/our-research/our-progress/.

- Montreal Clinical Research Institute, https://www.ircm.qc.ca/en/our-research.

- The Daily, Statistics Canada, Mental health-related disability rises among employed Canadians during pandemic, 2021 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220304/dq220304b-eng.htm.

- Club Vita, Reasons to be cheerful: progress in preventing dementia since my dad’s day, https://clubvita.ca/articles/article39.html.

- World Health Organization, Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy, https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/indicator-groups/indicator-group-details/GHO/life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy.

- The Press, What if all of Quebec was triple vaccinated?, https://plus.lapresse.ca/screens/210937ef-f51a-4b80-9b50-e90fdc39582e__7C___0.html?utm_content=email&utm_source=lpp&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=internal+share.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Working Age Population: Aged 15-64: All Persons for Canada [LFWA64TTCAM647S], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LFWA64TTCAM647S , April 1, 2022.

Shantel Aris, Longevity Risk Modeler, Club Vita Canada

Shantel has a diverse actuarial and statistical modelling background with over 5 years of pension, insurance, and reinsurance experience. She started her career in pension administration in Jamaica before pursuing her Master of Mathematics from the University of Waterloo, where she worked as a research assistant. She focused her graduate research on annuity designs with longevity risk sharing features. Shantel later co-authored the paper Greener Pastures: Resetting the Age of Eligibility for Social Security Based on Actuarial Science through the C.D. Howe Institute.

Shantel joined Club Vita in January 2021 to focus on supporting Club Vita’s Canadian and international research initiatives through modelling and experience analysis work. Also, Shantel has gained experience processing and assessing the quality of club member data submissions, as well as performing experience analysis based on club member data and preparing detailed longevity analytics reporting. In Shantel’s previous role, she spearheaded longevity data analytics, experience analysis, predictive modelling, and industry research at RBC Insurance to support the pricing of annuity reinsurance contracts.